Idle Thoughts – Fun With Remakes

Up until a few months ago, I’ve never really been a fan of podcasts for various reasons (mostly a lack of investment and interest in most “traditional” topics covered). Lately, though, I’ve taken to listening to the Retronauts one – headed by Jeremy Parish and Bob Mackey and featuring a variety of co-hosts in each episode, it’s billed as an “exploration of the history of video games” (with a specific focus on retro gaming). Needless to say, it’s a series I’d recommend wholeheartedly.

One of their most recent episodes revolved around a discussion on remastered/rebooted/remade games – including some very handy definitions of each – and it got me thinking. Looking back at the last six or so months, I realized that a lot of what I’ve been playing comes under one of these three categories – surprisingly in some cases, it’s also games that I never got to experience during their prime (i.e. the remake or remaster would be my very first direct contact with said game).

With that being said, let’s have a look at some examples, specifically of remakes, that I’ve played recently, either from a newcomer or an old timer’s perspective (depending on whether I’ve played a particular game’s previous iterations).

Striking Gold – Persona 4: The Golden

One of my biggest regrets in gaming is never having owned a Playstation 2 – partly due to low availability of units locally as well as a lack of funds at the time, I somehow managed to miss one of the biggest (and most influential) video game libraries of its time, much to my dismay. Although I eventually got an XBox and a Gamecube (the former second-hand and the latter at a severely discounted price) and was thus covered where multiplatform games were concerned, a PS2 and its huge list of exclusives would elude me for years.

That is, until the present culture of remakes/remasters emerged.

Among the many titles I had missed, one of my most wanted was the latter incarnations of the Persona series – Persona 3 and 4. Widely considered as some of the top JRPG’s of their time, mainly due to the unique blend of traditional JRPG systems and combat with a school life simulator, these two games were high on my list of “must-haves” – and with good reason.

Persona 3 initially received a remake for the PSP, titled Persona 3: Portable – a cut-down version of the original 2007 release (rather than the improved FES version from 2008) that removed exploration of the non-dungeon parts due to the limitations of the PSP, but with additional options, such as an option to play as a female protagonist and more direct combat control (where the original only allowed direct control of the protagonist in combat, where allies were AI-driven).

This set the stage for Persona 4: The Golden, which released for the PSVita in 2013, this time a fully realized and improved upon version of the original 2009 release. Needless to say, I was very excited about P4G – to the point that it was the reason I got a PSVita in the first place (and that decision was totally worth it, by the way).

While I’m no newcomer to the series, having played the first three games in various PSN re-releases during the PS3/PSP’s lifetime, I was definitely feeling like one for P4G – the first three games (Persona, Persona 2: Innocent Sin, Persona 2: Eternal Punishment) are quite different in terms of structure, systems and focus, taking on a more traditional JRPG form (albeit still within the series’ distinct “contemporary Japanese teen” theme), while from Persona 3 onwards we begin to see the now-familiar addition of everyday life simulation elements being added and slowly refined.

This made Persona 4: The Golden a very different experience for me. While I can’t really comment or compare the differences between versions (not having played the original PS2 title), I can wholeheartedly say that P4G was one of my standout JRPG experiences of the last few years – one that was only edged out by the even more amazing Persona 5 (which built and iterated on its predecessor’s already-refined formula). From the lovable cast of high school misfits to the lighthearted tone (which admittedly sometimes dives a bit deeper into darker places) to the excellent soundtrack, the deep and engaging combat and persona systems, the amazing voice acting (something that a lot of JRPG localizations often struggle with) – P4G was an exemplary experience in almost every aspect.

In Persona 4, as is typical of the series post-Persona 3, you take the role of a high-school student recently transferred to an unfamiliar town – Inaba, a small rural Japanese town, in this game’s case – where you are given one in-game year in order to resolve the game’s conflict. During the first couple of weeks, a series of bizarre murders forces you to recruit your fellow students into a ragtag bunch dubbed the Investigation Team, with the goal of solving the mystery behind these crimes.

While I could go on for several paragraphs extolling P4G’s virtues (and there are a lot of those), in the interest of brevity (and covering other games as well) I’ll just limit myself to this: while most of the game’s design ranges from great to stellar, special mention must be given to the character development and design. It’s a rare game that makes me feel like I’m invested in (and maybe bonded with) any characters, and an even rarer one that does so with the entire cast. Indeed, around 90 hours of playtime later, I can easily name most, if not all, of the game’s main cast, as well as several of the supporting cast (dubbed Social Links), as well as their backstories, character traits, speech patterns and mannerisms and so on and so forth.

Persona 4 Golden is an incredible accomplishment, a must-play JRPG that, going by fan reactions, managed to improve upon an already excellent base – with many additions, improvements and streamlined content, an excellent example of a remake done right.

On the very flip-side of Persona 4: Golden, let’s have a look at a game I’ve played the original release but had never managed to experience the remake of, until modern re-releases enabled me to do thus…

Travels in Time – Journeyman Project: Pegasus Prime

The Journeyman Project (subtitled Turbo, after several performance-enhancing fixes were made) is a first-person point-n-click adventure game in the vein of Myst, but with a decidedly more sci-fi feel to it. First released in 1994 (with original, non-Turbo version launching a year prior), it was one of the first 3D games I ever played – even if said 3D consisted primarily of pre-rendered objects and backgrounds with chroma-keyed actors overlaid – and one I immediately fell in love with.

I’ve always attributed my wide love of gaming genres to my initial experiences – in close succession, I had been exposed at a very young age to the faster-paced platform action of Super Mario Land (on a friend’s Gameboy before getting one of my own), as well as the more logic-oriented slow pace of text adventures such as Zork and Enchanter (well past their prime but part of the very small pool of available games for a 486 running DOS). In Journeyman Project Turbo, I probably found for the first time a meeting of the two worlds, with the urgency of an action game conveyed by the game’s story, fused expertly with the slow, methodical mechanics of an adventure game – which is presumably why I was so taken in by it.

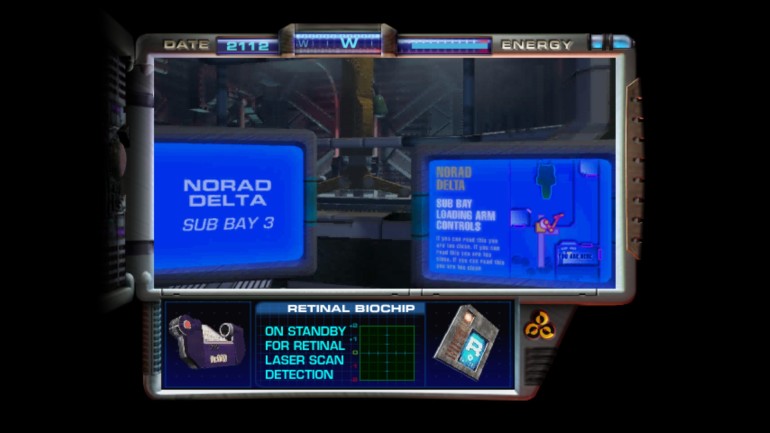

You take the role of Gage Blackwood and it’s the near future – a future where time travel is not only available but also heavily regulated. Gage is part of the TSA, the Temporal Security Annex, a government organization tasked with policing time itself… until everything goes wrong. Narrowly managing to escape temporal catastrophe, Gage must now locate where (and more importantly, when) it all went wrong, then travel back in time in order to change the past and save the future.

As far as game mechanics go, Journeyman Project is a more or less standard adventure game – solve puzzles and collect items to access new areas, repeat until end of game. As with many of its time, where it shines is in atmosphere, presentation and story beats. The time-travel angle is explored in sufficient depth – not too jargon-laden, but not glossed over either – and the whole “choose which order to play the levels/locations in” approach was unique for adventure games at the time (even if in actuality it’s a fairly linear game) and further worked to reinforce the temporal themes.

As mentioned before, I had only played the original (Turbo) release back when I was younger – the 1997 remake was a Mac-exclusive title up until a few years ago, where it made a surprising appearance on PC’s via GOG and Steam – so going into Pegasus Prime was quite the interesting experience.

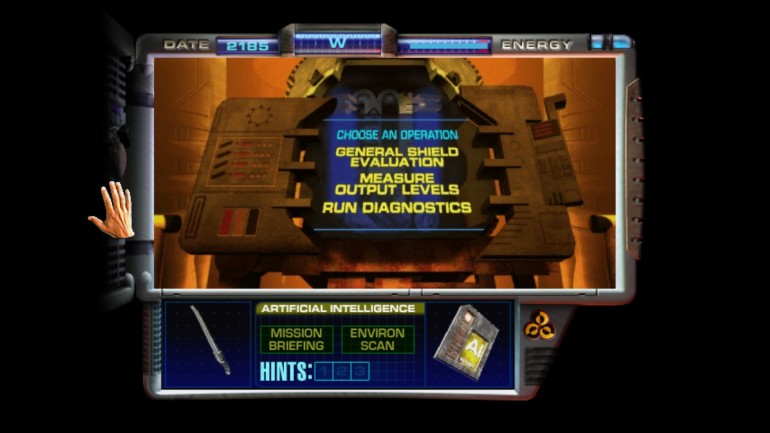

The first thing that drew my attention was the redesigned UI. While both the Turbo and Pegasus Prime versions have comparatively tiny viewports from which players can see the world, PP’s one is decidedly less intrusive, enlarged and higher resolution. Adding to that a much more smoothly animated inventory/chip system meant that the game as a whole felt smoother and slicker than I had remembered.

Additionally, with Pegasus Prime, the developers would go on and re-film actors and locations, giving the visuals a much-needed upgrade with protagonist Gage Blackwood in particular now having a fully-animated (filmed) presence in-game, as opposed to static portrait photos in the original. Additionally, where in the original Gage was pretty much the only person to be seen physically in the world, Pegasus Prime adds a couple new actors to the mix, one of which ties to later games in the series – which made a small nod to continuity possible and got a chuckle out of series fans such as myself.

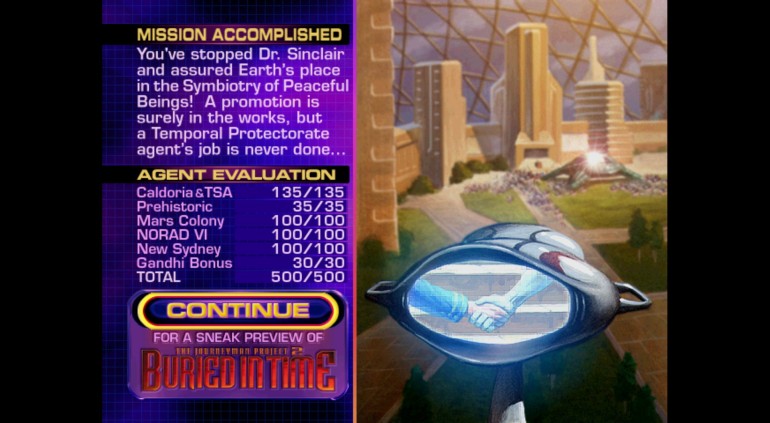

The improvements didn’t stop there, though. Several systems were revamped, with movement in particular being smoother and feeling more animated – no doubt thanks to higher resolution imagery used – while the score system was now more descriptive and comprehensive (as with many adventure games of the time, there is a score system – see further examples in any Sierra game of that time, where a completed game did not necessarily award full points unless optional actions and interactions were found).

Finally, the biggest change was the expansion and, in some cases, total overhaul of certain areas in the game – mostly quality-of-life improvements such as shortcuts being added and areas being rendered with slightly different layouts to better indicate interactions, but also changes in some puzzles to eliminate a kind of “leap in logic” style of gameplay that was sadly prevalent in adventure games of the time (which is not to say that Journeyman Project is totally free of those puzzles, but it fares a lot better than most of its contemporaries).

While the game (in both incarnations) has aged poorly – understandably so, since Turbo came out in ’93 and Pegasus Prime in ’97 – I’d still hold it as one of the best examples of how to remake a game: adding functionality, accenting strengths and correcting weaknesses in the design, with the aim of bringing the product up to spec for a more modern audience and more capable hardware. Indeed, where most other games would try to reinvent the wheel, so to speak, Journeyman Project took the much better route of refining what was already there – thus making it a memorable experience and one of the more refined first-person adventure games of its time that I’ve ever played.

In Conclusion…

Looking back at this article, I haven’t even began to scratch the surface of all my favorite remakes and when also considering remasters and reboots, the topic seems to stretch infinitely – between ensemble collections like Kingdom Hearts, former genre juggernauts such as Baldur’s Gate and oddball remakes like Chronicles of Riddick, there is just so much more to discuss. Perhaps, in time, we’ll take another look…

Do you enjoy remakes and remasters? Ever played one? Have a story to share about your most or least favorite remakes of old classics? Perhaps you hate the entire idea of them and want to talk about it? Drop a line in the comments and let me know!

One thought on “Idle Thoughts – Fun With Remakes”